A bad month for share prices made relatively little impact on investors in May, according to the latest Fund Flow Index (FFI) from Calastone, the largest global funds transaction network, but mainly because buyers have been on strike now for months. Having shunned equity funds for six months in a row, investors showed that they still preferred to sit on the sidelines as share prices fell, just as they had during the market rebound earlier in 2019. The FFI: Equity registered 50.5 in May, staying very close to the neutral 50 mark where it has been since December. In total, investors bought a net £155m of equity funds, a fraction of the long-run monthly average of £750m.

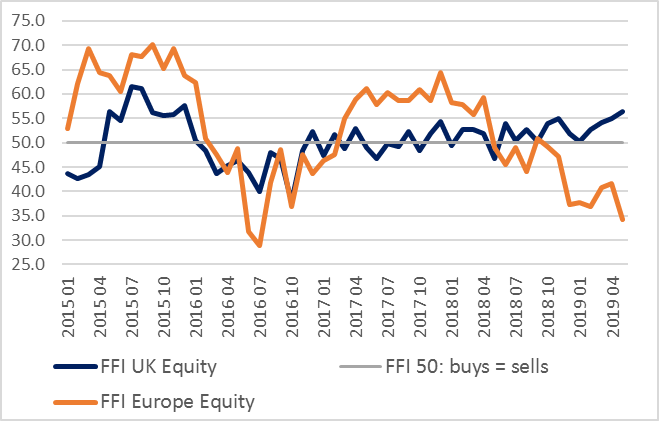

Figure 1: FFI UK Equity v FFI European Equity

The overall neutral stance belies considerable divergence between the different types of equity fund, however. Most categories saw outflows, with European funds again faring worst. Net outflows rose to £410m in May, the second worst month on record after July 2016, when the Brexit referendum result spooked investors. The FFI: European Equity plunged to 34.2, as the value of sell orders reached almost double the value of buy orders. Over the last 12 months, £2.1bn has left funds focused on European shares. Meanwhile, UK equity funds enjoyed the largest inflows since August 2015. £404m flowed into the sector in May, the twelfth consecutive month where buys have exceeded sells, and taking the total inflow over the last 12 months to £2.2bn, almost exactly matching the outflow from European funds. The FFI: UK Equity showed a very positive 56.5. In fact, without investors’ strengthening appetite for the UK, equity funds would have seen outflows in five of the last six months, rather than an approximate balance between buying and selling that has kept the FFI: Equity close to the neutral 50 mark. Global funds also continued to enjoy inflows.

Overall, investors shunned high-risk funds. In May, outflows from the riskiest bands of funds reached their highest level since October 2016, just before the US presidential election. High-risk funds have now seen outflows in five of the last six months.

Figure 1: FFI UK Equity v FFI European Equity

The overall neutral stance belies considerable divergence between the different types of equity fund, however. Most categories saw outflows, with European funds again faring worst. Net outflows rose to £410m in May, the second worst month on record after July 2016, when the Brexit referendum result spooked investors. The FFI: European Equity plunged to 34.2, as the value of sell orders reached almost double the value of buy orders. Over the last 12 months, £2.1bn has left funds focused on European shares. Meanwhile, UK equity funds enjoyed the largest inflows since August 2015. £404m flowed into the sector in May, the twelfth consecutive month where buys have exceeded sells, and taking the total inflow over the last 12 months to £2.2bn, almost exactly matching the outflow from European funds. The FFI: UK Equity showed a very positive 56.5. In fact, without investors’ strengthening appetite for the UK, equity funds would have seen outflows in five of the last six months, rather than an approximate balance between buying and selling that has kept the FFI: Equity close to the neutral 50 mark. Global funds also continued to enjoy inflows.

Overall, investors shunned high-risk funds. In May, outflows from the riskiest bands of funds reached their highest level since October 2016, just before the US presidential election. High-risk funds have now seen outflows in five of the last six months.

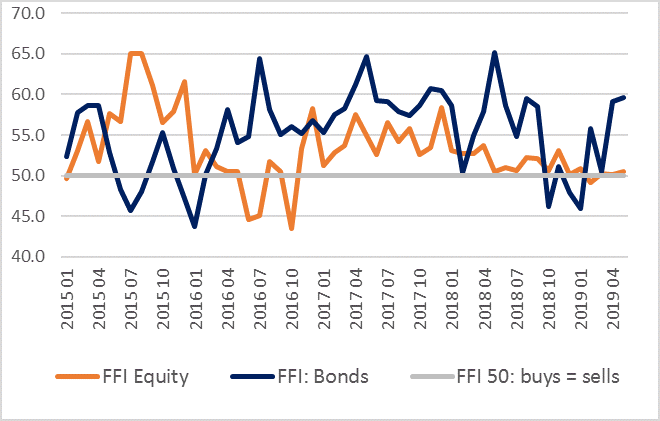

Figure 2: FFI Equity v FFI Bonds

Bond funds were the main beneficiaries of risk aversion among investors. Managers of fixed income funds enjoyed the fifth best month on record as £845m of new capital flowed in. The FFI: Bonds rose to 59.8, the highest reading in over a year.

Elsewhere, the pace of outflows in real estate funds continued to slow, although investors nevertheless withdrew property fund holdings for a record eighth consecutive month. This was driven mainly by a reduction in selling activity, rather than an uptick in buyer appetite.

Finally, the flow of funds offshore slowed sharply in May. Net purchases of offshore funds mainly registered in Luxembourg and Dublin, halved month-on-month in May, having halved already in April. Net purchases were £553m, down from £3.1bn in February.

Edward Glyn, Calastone’s head of global markets said: “Global markets had a terrible month in May as investors absorbed the blows traded by China and the US in their growing trade war. Investors in equity funds have sat on the sidelines now for six months in a row, longer than we have ever seen before in our Fund Flow Index. This is despite relatively busy two-way trading, meaning that, while investors are happy to switch between their holdings, they are not prepared to commit new capital. But this is not to say they are treating all types of equity funds with the same disdain. UK equities have seen inflows rise month by month all year, as more and more investors have come to recognise how cheap the UK market has become relative to its global peers. Meanwhile, there’s no respite for European funds – relentless outflows are accompanying growing pessimism about the outlook for the economy there. If you strip out the UK, it’s clear that equities have lost their lustre for the time being.

Rising risk aversion is pushing investors back to the safety of bonds. Global yields have dropped to their lowest level in 18 months, and the US yield curve is inverted, often a signal of a sharp slowdown in economic growth. Expectations of interest rate cuts push bond prices higher, so investors can benefit from capital gains as well as the relative safety of sovereign issuers.

Finally, the slowdown in the flow of money offshore is closely related to the Brexit saga. The UK has kicked its EU departure further down the political road. At each sign of delay, investors show less appetite to place capital outside the UK’s regulatory orbit.”

Figure 2: FFI Equity v FFI Bonds

Bond funds were the main beneficiaries of risk aversion among investors. Managers of fixed income funds enjoyed the fifth best month on record as £845m of new capital flowed in. The FFI: Bonds rose to 59.8, the highest reading in over a year.

Elsewhere, the pace of outflows in real estate funds continued to slow, although investors nevertheless withdrew property fund holdings for a record eighth consecutive month. This was driven mainly by a reduction in selling activity, rather than an uptick in buyer appetite.

Finally, the flow of funds offshore slowed sharply in May. Net purchases of offshore funds mainly registered in Luxembourg and Dublin, halved month-on-month in May, having halved already in April. Net purchases were £553m, down from £3.1bn in February.

Edward Glyn, Calastone’s head of global markets said: “Global markets had a terrible month in May as investors absorbed the blows traded by China and the US in their growing trade war. Investors in equity funds have sat on the sidelines now for six months in a row, longer than we have ever seen before in our Fund Flow Index. This is despite relatively busy two-way trading, meaning that, while investors are happy to switch between their holdings, they are not prepared to commit new capital. But this is not to say they are treating all types of equity funds with the same disdain. UK equities have seen inflows rise month by month all year, as more and more investors have come to recognise how cheap the UK market has become relative to its global peers. Meanwhile, there’s no respite for European funds – relentless outflows are accompanying growing pessimism about the outlook for the economy there. If you strip out the UK, it’s clear that equities have lost their lustre for the time being.

Rising risk aversion is pushing investors back to the safety of bonds. Global yields have dropped to their lowest level in 18 months, and the US yield curve is inverted, often a signal of a sharp slowdown in economic growth. Expectations of interest rate cuts push bond prices higher, so investors can benefit from capital gains as well as the relative safety of sovereign issuers.

Finally, the slowdown in the flow of money offshore is closely related to the Brexit saga. The UK has kicked its EU departure further down the political road. At each sign of delay, investors show less appetite to place capital outside the UK’s regulatory orbit.”

Methodology

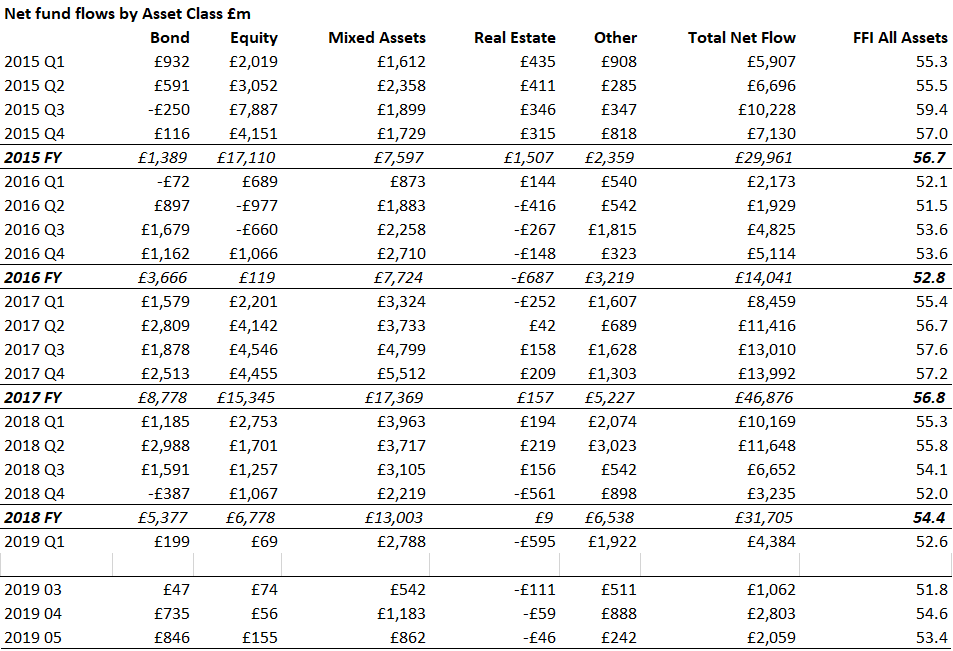

Calastone analysed over a million buy and sell orders every month from January 2015, tracking monies from IFAs, platforms and institutions as they flow into and out of investment funds. Data is collected until the close of business on the last day of each month. A single order is usually the aggregated value of a number of trades from underlying investors passed for example from a platform via Calastone to the fund manager. In reality, therefore, the index is analysing the impact of many millions of investor decisions each month.

More than two thirds of UK fund flows by value pass across the Calastone network each month. All these trades are included in the FFI. To avoid double-counting, however, the team has excluded deals that represent transactions where funds of funds are buying those funds that comprise the portfolio. Totals are scaled up for Calastone’s market share.

A reading of 50 indicates that new money investors put into funds equals the value of redemptions (or sales) from funds. A reading of 100 would mean all activity was buying; a reading of 0 would mean all activity was selling. In other words, £1m of net inflows will score more highly if there is no selling activity, than it would if £1m was merely a small difference between a large amount of buying and a similarly large amount of selling.

Calastone’s main FFI All Assets considers transactions only by UK-based investors, placing orders for funds domiciled in the UK. The majority of this capital is from retail investors. Calastone also measures the flow of funds from UK-based investors to offshore-domiciled funds. Most of these are domiciled in Ireland and Luxembourg. This is overwhelmingly capital from institutions; the larger size of retail transactions in offshore funds suggests the underlying investors are higher net worth individuals.

Methodology

Calastone analysed over a million buy and sell orders every month from January 2015, tracking monies from IFAs, platforms and institutions as they flow into and out of investment funds. Data is collected until the close of business on the last day of each month. A single order is usually the aggregated value of a number of trades from underlying investors passed for example from a platform via Calastone to the fund manager. In reality, therefore, the index is analysing the impact of many millions of investor decisions each month.

More than two thirds of UK fund flows by value pass across the Calastone network each month. All these trades are included in the FFI. To avoid double-counting, however, the team has excluded deals that represent transactions where funds of funds are buying those funds that comprise the portfolio. Totals are scaled up for Calastone’s market share.

A reading of 50 indicates that new money investors put into funds equals the value of redemptions (or sales) from funds. A reading of 100 would mean all activity was buying; a reading of 0 would mean all activity was selling. In other words, £1m of net inflows will score more highly if there is no selling activity, than it would if £1m was merely a small difference between a large amount of buying and a similarly large amount of selling.

Calastone’s main FFI All Assets considers transactions only by UK-based investors, placing orders for funds domiciled in the UK. The majority of this capital is from retail investors. Calastone also measures the flow of funds from UK-based investors to offshore-domiciled funds. Most of these are domiciled in Ireland and Luxembourg. This is overwhelmingly capital from institutions; the larger size of retail transactions in offshore funds suggests the underlying investors are higher net worth individuals.